Getting Things Done

If you dive into the wild world of personal productivity advice, sooner or later you’re going to come across David Allen’s book Getting Things Done: The Art of Stress-Free Productivity .

Getting Things Done outlines “GTD”, a method of personal organization that builds “the new mental skills needed in an age of multitasking and overload”, growing from a productivity method into a global movement.

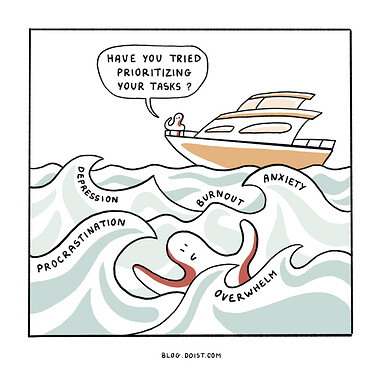

In a chaotic world with ever-increasing demands on our time and attention, Allen’s methodology promises nothing less than a complete sense of calm and control over your life. Who doesn’t want that?

The problem is, GTD is complicated. At one point in the book, Allen states “The right amount of complexity is whatever creates optimal simplicity”. But often complexity just creates more complexity. Many a GTDer has found that maintaining their system becomes a project unto itself.

I’ve tried to GTD several times over the years. I’ve never kept it up for more than a month. Yet, I can still say that Getting Things Done is one of a small handful of books that has literally changed my life. Here are three GTD principles that I believe everyone should know about, whether you adopt Allen’s system in its entirety or not:

1. Don’t keep track of your “incompletes” in your head

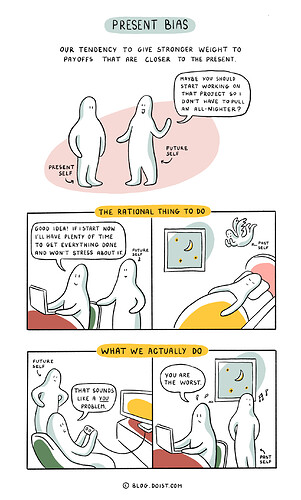

At the crux of GTD is the insight that our brains continually remind us about our pending commitments, even when we can’t do anything about them (see the Zeigarnik Effect). This mental tension creates a background level of stress in our lives, making it all the harder to get anything done.

GTD asks you to take all of the stuff rattling around in your brain — “all the things you consider incomplete in your world — that is, anything personal or professional, big or little, of urgent or minor importance, that you think ought to be different than it currently is and that you have any level of internal commitment to changing” — and write it down in a place that you will review daily.

You might be thinking: Allen’s brilliant idea is to… keep a to-do list? Fair enough. But his description is a radically different way of thinking about the true purpose of a task list. After reading Getting Things Done, I started to see my to-do list not (just) as a way to remind myself what needs doing, but as a tool for mental clarity, focus, and even self-care. Viewed this way, I’m motivated to make time for it especially when I feel like I don’t have the time.

2. Follow the Two-Minute Rule

Here’s an in-depth article on Allen’s Two-Minute Rule that I highly recommend, but here’s the essence of it: If a task will take two minutes or less to do, do it right away.

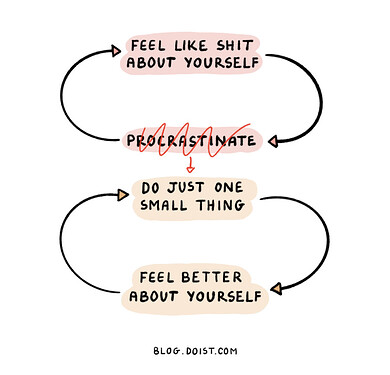

“Often it’s small tasks that pile up on our to-do lists, fill us with dread, and eventually feel insurmountable. Generally speaking, responding to an email, watering a plant, tidying your desk, filing a receipt, or wiping down a mirror are all tasks you can complete in 120 seconds or less. But, taken together and left to collect, they add up to a laundry list of chores that we continually put off. As a result, we spend more time and energy thinking about how we haven’t done them yet and feeling guilty about it than we would have spent just doing the things in the first place.”

Bottom line: If a task takes less than two minutes, it’s not worth thinking about doing it and then thinking about not having done it and then thinking about doing it again. Just do it.

3. Constantly ask yourself “What’s the next physical action?”

We tend to think about our commitments in vague terms: Clean the garage, do my taxes, attend the conference. The problem is, when you set out to do a task like “clean the garage”, you still have to decide where exactly you’ll start, which makes it harder to get started at all.

From Getting Things Done:

“If you haven’t identified the next physical action required to kick-start [a task or project], there will be a psychological gap every time you think about it even vaguely. You’ll tend to resist noticing it, which leads to procrastination. When you get to a phone or to your computer, you want to have all your thinking completed so you can use the tools you have and the location you’re in to more easily get things done, having already defined what there is to do.”*

Here are some examples Allen gives of possible next actions:

- Clean the garage → Call John re: refrigerator in the garage

- Do my taxes → Waiting for documents from Acme Trust

- Attend the conference → E-mail Sandra re: press kits for the conference

When you start thinking about your to-do list in terms of the next, physical action, it becomes a lot less intimidating to get started. (I make use of Todoist, and I find sub-tasks are incredibly handy for defining next actions).

There are many more productivity gems in Getting Things Done that make it well worth the read. I think everyone should attempt to GTD at least once in their lives. You’re bound to learn a lot whether you stick with it or not.

Just thought I would share some insights and findings that I have found to help me in this chaos of work and life and providing me to build systems that work for me. Share some of your thoughts and systems that work for you.

), I have rolling reporting deadlines. But at home we can put small maintenance tasks off for months.

), I have rolling reporting deadlines. But at home we can put small maintenance tasks off for months.